- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States

Who owns the freed slave's corpse?

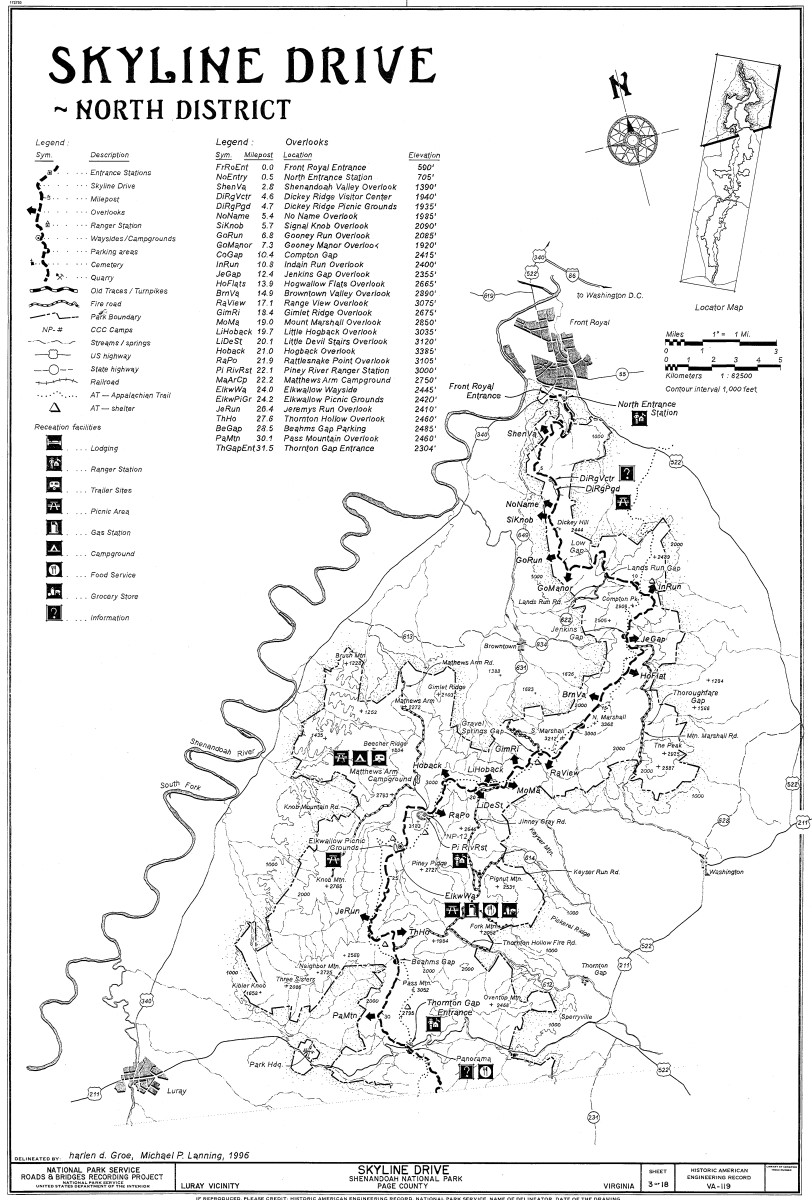

The story of Freedom House Slave Museum, once the largest slave market on the east coast, is inextricably tied to the stories of Alexandria National (also called “Soldiers”) Cemetery, a few blocks south, and Freedmen’s Cemetery a few blocks farther south and east.

After seizing the city, Union troops had converted the Franklin and Armfield slave market compound to a jail. In 1864, the jail was converted to the 600-bed L’Ouverture Hospital (After Toussant L’Ouverture who led the slave rebellion in Haiti at the end of the 18th century).

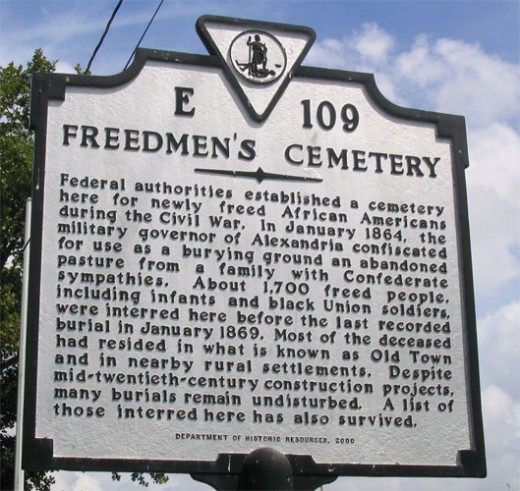

From its inception, Alexandria’s Freedmen’s Cemetery—also known as the Contraband Burying Ground—has been different from most graveyards. The term “contraband” originated farther south, when runaway slaves sought refuge at Union-held Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia, As Confederate slave owners demanded their return as required by the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, Major General Benjamin Butler, Fort Monroe’s commanding general, declared that the Fugitive Slave Law was United States federal law. By seceding from the Union, slave-holders in the Confederate states had lost its protection. He declared the runaway slaves contraband of war.

African Americans had lived in Alexandria since the city was founded in the previous century. They included servants, field hands and freed men. They had helped to clear and work the fields and to build the homes and barns and warehouses, Many of them had been freed by plantation owners who could no longer afford them when their crops began to fail.

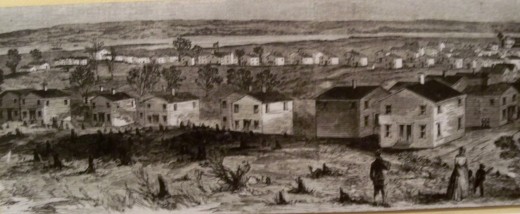

The Civil War added to the population of freedmen when the United States government, including the army, employed this human contraband that had made its way to the safety of a Union held town, either as labor or as United States Colored Troops. Like Fort Monroe, Alexandria had remained in Union hands throughout the war and became a magnet for these runaway slaves as they sought freedom. War is hard on troops and civilian alike, but these refugees were penniless and malnourished and lived wherever they could find shelter. The government constructed some contraband barracks but infant mortality rates ran high, and smallpox and typhoid claimed thousands of Alexandria’s African lives, and sometimes their shelter was an abandoned building or a hastily built shanty.

Of course that did not mean that they were considered equal to their white counterparts, and as the freed slaves resident in Alexandria, whether from natural causes, rampant disease or wounds of war, the government had to provide land for their burial. At that time, few would suggest that freed slaves be buried alongside white casualties, so. In 1864, the Reverend Albert Gladwin, the city’s African American Superintendent of Contrabands, and Military Governor Brigadier General John P. Slough commandeered a parcel of undeveloped land at Church and South Washington streets, from its pro-Confederate owner, a lawyer named Francis L. Smith. So it was that The Contraband Burying Ground was consecrated a few blocks southeast of the Alexandria National Cemetery.

The Freedmen’s Cemetery was an active burial ground only for about five years, and not without controversy. That controversy reached its climax with a bizarre funeral hijacking and a mass protest at a nearby Army hospital.

As Superintendent of Contrabands, the Rev. Mr. Gladwin insisted that all African American soldiers were to be buried in the Contraband Cemetery instead of the Soldiers’ Military Cemetery. The African American troops in the town’s hospitals wanted to be buried with their comrades in arms in Soldiers’ Cemetery. Captain J.G.C. Lee, the Assistant Depot Quartermaster at L’Ouverture, believed that all deceased U.S. soldiers, including African Americans, were to be buried at Soldiers’ Cemetery at the west end of Wilkes Street.

Gladwin was insistent and obtained an order from the Military Governor, confirming that all black soldiers were to be buried in the Contraband Burying Ground.

Captain Lee was equally insistent that all soldiers should be buried on U.S. property. Setting aside a separate area for black soldiers, Lee ordered that all soldiers be buried at Soldiers Cemetery.

Rev. Gladwin, determined to prevail, arrested the driver of a hearse carrying the remains of an African American soldier to Alexandria National Cemetery, and redirected the funeral to Contraband Cemetery, where the soldier was buried.

In December 1864, 443 soldiers recuperating at L’Ouverture petitioned to be buried along with their fellow soldiers. “We are not contrabands, but soldiers of the U.S. Army,” they said. They asked that their “bodies may find a resting place in the ground designated for the burial of the brave defenders of our countries [sic] flag.”

Captain Lee appealed to General Slough, who said that he would abide by the decision of Major General M.C. Meigs, the Quartermaster General whose responsibilities included military hospitals. Captain Lee sent the L’Ouverture soldiers’ petition along with his written appeal to General Meigs. Apparently, Meigs found his argument compelling, because Gladwin was removed from his position and Lee resumed burying all soldiers, including blacks and Native Americans, in Soldiers’ Cemetery.

In January 1865, the remains of about 220 black veterans were moved from Freedmen’s Cemetery to the Soldiers’ Cemetery, where 37 regiments of U.S. Colored Troops, including five of the renowned Buffalo Soldiers, are interred.

Until President Andrew Jackson disbanded the Freedmen's Bureau in December 1869, the Bureau assumed responsibility for the Contraband Burying Ground after the end of the war. In 1869, the cemetery was closed and the land, with about 1,700-1,800 graves, reverted to its previous owner.

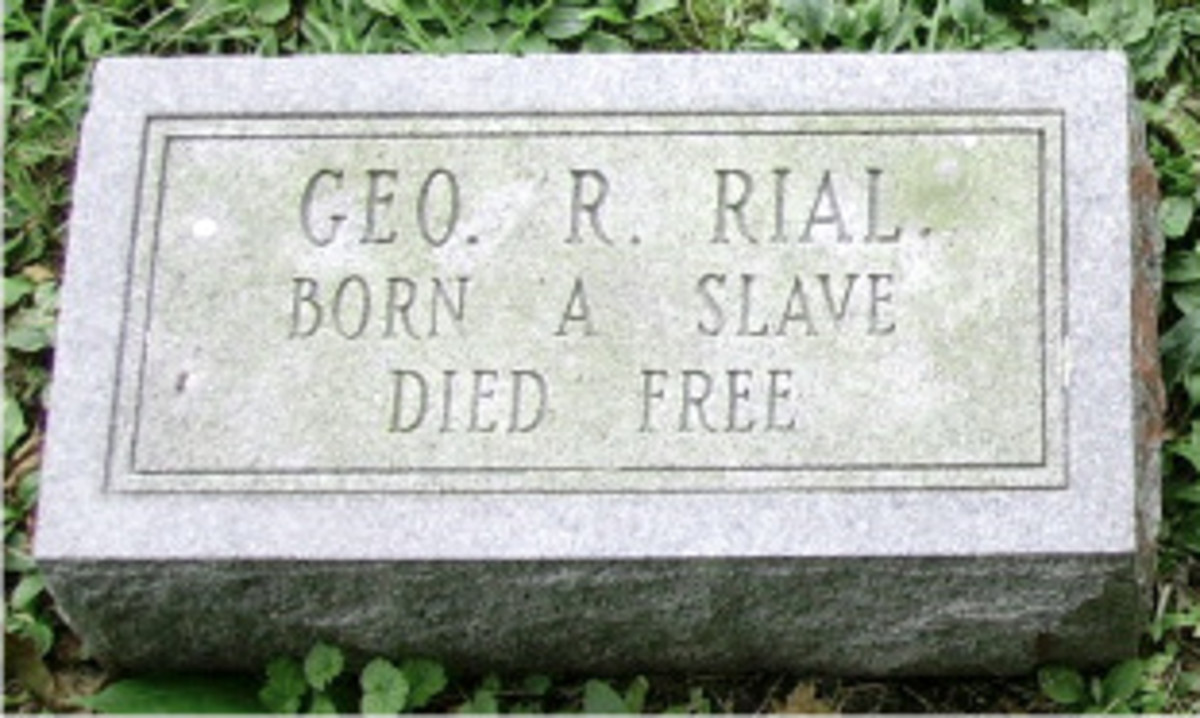

Over time, the wooden grave markers rotted away and were not replaced, unlike Soldiers’ Cemetery, where permanent grave stones replaced the whitewashed boards

The land changed hands several times in the twentieth century. The forgotten and unmarked burial ground hosted a gas station and then an office building. In 1987, interest in the site was aroused when a city historian discovered a newspaper article that referred to a graveyard on the site. In 1994, Gladwin’s burial log was discovered, confiirmng the earlier finding.i

When the gas station and office building on the site were razed in 2007, city archaeologists discovered evidence that the land had been a prehistoric site. They also discovered a grave, which they left undisturbed.

In May 2007, the Freedmen’s Cemetery was rededicated, and plans to develop a commemorative park on the site are underway.

For more information, visit http://www3.alexandriava.gov/freedmens.